Balinese traditional art

Holstebro Kunstmuseum’s collection of Balinese traditional art is a gift from the artists, the married couple Agnete Therkildsen and Ejler Bille, who since the 1970s stayed in Bali several times.

Ejler Bille (1910-2004) and Agnete Therkildsen (1900-93) were enthusiastic travellers who journeyed around Europe, North Africa and China. Bali, however, became a very special place for them, and their Balinese collection was built up over a long period of time. It consists of items acquired on the island from 1972 onwards, including artworks purchased for Holstebro Municipality for the museum from early 1974, when it was decided – through the mediation of the then museum consultant Poul Vad – that “the collection of Balinese art would be a very exciting and unusual addition to the museum.” The artist couple had been visiting Bali since 1970, and their private collections were transferred to the museum on an ongoing basis via letters of donation in 1973, 1977 and 1981.

Ejler Bille & Agnete Therkildsen's Balinese colletion

Bille’s own abstract surrealist art was already represented in the museum at this time, and because Vad wished the museum’s collection to create a space for artistic dialogues across time and space, the decision to donate the collection was obvious. In this sense, the Balinese collection points to the links, both artistic and human, that exist between a modernist avant-garde artist and traditional Balinese art.

Right from the opening of the museum in 1967, a loaned selection of items from sculptor Poul Holm Olsen’s collection of traditional African art was included in its permanent exhibition, but Bille and Therkildsen’s Balinese collection was the first collection with roots outside Western culture to be formally inventoried at the museum.

Bille donated the final item to Holstebro Kunstmuseum in 1998, and a further 53 items were subsequently donated after Bille’s death in 2004. Today, the collection comprises a total of 213 main item numbers, behind which lies a whole universe populated by painted wooden figures of gods, heroes and demons, masks, temple fixtures, tapestries, astronomical calendars and shadow play figures.

Dance and drama

Bali’s many forms of dance and drama play a crucial role. They originally developed in the 11th century when Hindus came to the island and mingled with the original culture. In the 16th century a further wave arrived, consisting of aristocrats and artists who had fled Java and the Muslim princes. They brought with them their ancient Hindu-Javanese court culture, which can be traced in the sophisticated Balinese choreography and mask art, performances on literary models and the diversity of melodic and rhythmic structures of the so-called gamelan orchestras.

Although Hindus constitute a national minority in Indonesia, as many as 85% of Balinese are Hindu, with hybrid rituals that also incorporate elements of Aga animism and Indian Buddhism. A portion of the items in the collection may be attributed to folk art as it is practised in the island’s mountainous regions. This everyday art has a different character to the refined court art of the lowlands, although these are interconnected, including in practice. They tell of a complex culture in which life, mythology and art are completely inseparable.

A world, where everything has its place

Contrary to the rest of Indonesia, which is Muslim, Bali is Hindu. Hinduism was introduced to Bali in the 5th century, and around 1500 most Balinese were Hindus. The Balinese Hinduism is a synthesis of the island’s original tribal religion and Javanese Hinduism, where the worship of Shiva, who is both a fertility god and the great destroyer, is central.

The Hindus in Bali live in a world, where everything has its place. It is based upon the contrast between Kaja and Kelod. Kaja represents the direction towards the mountain, where the gods live, and Kelod represents the direction towards the sea, where the demons and evil belong. In between these two opposing forces lives mankind. This conception is also reflected in the structure of the temples. They are composed of three courtyards representing each of the three areas.

The Balinese worship many gods. But in reality they regard all the gods as different aspects of one supreme god called Sanghyang Widi Wasa: In the shape of Ris Dewi Sri it is a fertility god and attached to the mountain, and in the shape of Dewa Baruna it is the destroyer and attached to the sea.

The Balinese do not make representations of their gods. In many temples there is a sanctuary with three empty seats for Shiva, Brahma and Vishnu. The Balinese imagine that they sit here during the ceremony.

Shadow play, Wayang-Kulit

One of the Balinese people’s ways of visualising the religious practice is the shadow play (Wayang Kalit) and through the many dances directed against demoniacal forces. The dancers carry masks and costumes identifying them as a fabled, lion-like creature, Barong, who is capable of driving out evil spirits, or as Ranga, evil itself.

Wayang was included in UNESCO's Intangible World Heritage List in 2003 and constitutes a rich and living tradition in Bali, Java and Lombok. The word wayang actually means 'shadow' or 'imagination' in Javanese, but is used as a term for both the individual puppet and the theater form itself. Kulit means 'hide' or 'skin' and refers to the form of wayang where the figures are flat and created from buffalo leather.

Ejler Bille and Agnete Therkildsen's Balinese collection contains a total of 10 different wayang characters. They are lit from behind for the performances. As a rule, there is only one light source behind the canvas fabric, which can consist of anything from incandescent bulbs to oil lamps. Wayang is performed in the evening and at night and can last up to nine hours. The dalang, the puppeteer, controls all the puppets himself, and the drama is accompanied by the indispensable gamelan orchestra. Although the audience only sees the silhouettes, the figures are respectfully and artfully executed with rich carvings, painting and gilding.

Wayang is most often about the struggle between good and evil and draws on Hindu mythology and epic poetry shared by the Balinese. Broadly speaking, there are two main sources: the Indian epic Ramayana (Sanskrit for 'the story of Rama') from c. 400-200 BCE, which consists of 24,000 couplets spread over seven books and the Sanskrit poem Mahabharata ('the great Bharata dynasty'), which is a heroic poem from ca. 400 BCE-400 CE and consists of approx. 100,000 couplets spread over 19 books. Although the Mahabharata is a heroic story, it is full of religious teachings as well as ethical and philosophical considerations, the main theme of which is the fulfillment of the eternal lawfulness, dharma. The blend of fairy tales and spiritual guidance makes it popular and suitable for film adaptations, dances, TV series, plays and songs.

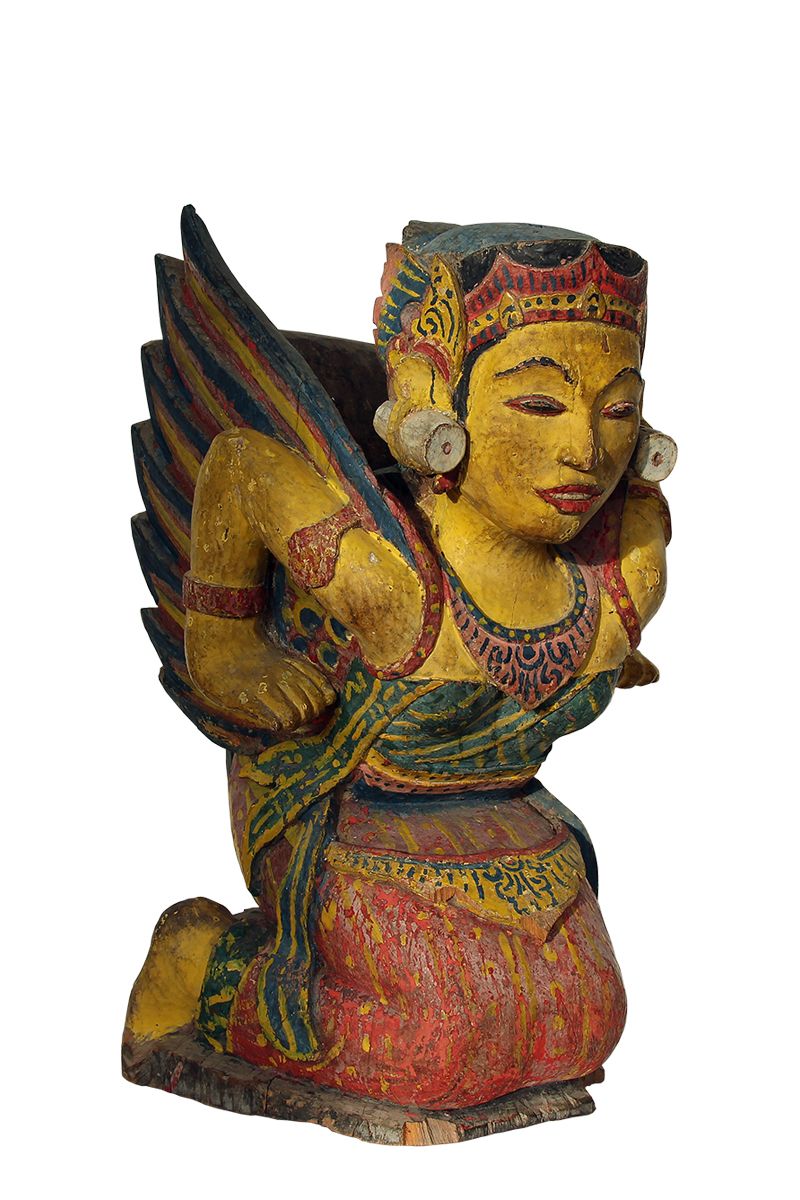

Woodcarving and paintings

The Balinese woodcarving art consists of reliefs and freestanding figures and mainly depicts demons, heroes and local deities. Pavilions are often decorated with a garuda – the golden eagle that Vishnu rides – or with a winged lion – a singha. Both figures are considered to be auspicious. Other popular wooden sculptures are the monkey hero Hanuman from the great Hindu epic Ramayana, and small Sri figures that protect the rice harvest.

The paintings are tapestry-like cartoons, which are often used for decorating temples. They depict scenes from the legends, or they are religious calendars with motifs from the holy Wuku year’s cycle of 210 lucky and unlucky days. On the temple walls hang narrow cloth hangings (Ider-Ider), which can be painted with religious and mythological scenes.

"You’re in Bali, you’re really back in Bali!

Soon you’ll be able to hear the gamelan orchestra, the xylophones, the great gong, the slender reed flutes […] Us, we’re like a pair of old migratory birds that always return to the same nesting place. In our case, that means Puri Kantor. Nenek and Kakek , grandfather and grandmother, is what Anton tells us they are calling us in the village"

Ejler Bille, 1993